The Legacy of Racism and the Success of Donald Trump

When you pass from Selma to Montgomery in the state of Alabama it’s all about history, from slavery to Civil Rights, from decayed sharecropper houses to impressive Memorial Sites. You also feel that it is all about racism, from the historic march across Edmund Pettus Bridge in March 1965 to the repeated election victory of Donald Trump in November 2024. What has changed? On this 54-mile-long journey you see the markers of white supremacy and black despair, of black dignity and white fear, you meet African Americans disheartened by recent political changes and hear stories of white resentment feeding the conservative backlash. It reads like a continuous story of two tribes losing.

In front of “Brown Chapel Church AME” in Selma Reverend Alvin C. Bibbs instructs the two dozen disciples of his guided tour in the rules of their short symbolic march from the church to Edmund Pettus Bridge. “Take water and walk slowly in the sun”. But where the members of this tourist group visiting from Chicago are wearing comfortable sneakers the freedom fighters of 1965 had only their ordinary shoes to leave the church, cross the bridge and walk onwards to Montgomery on their four-day-long march that changed not only Southern history.

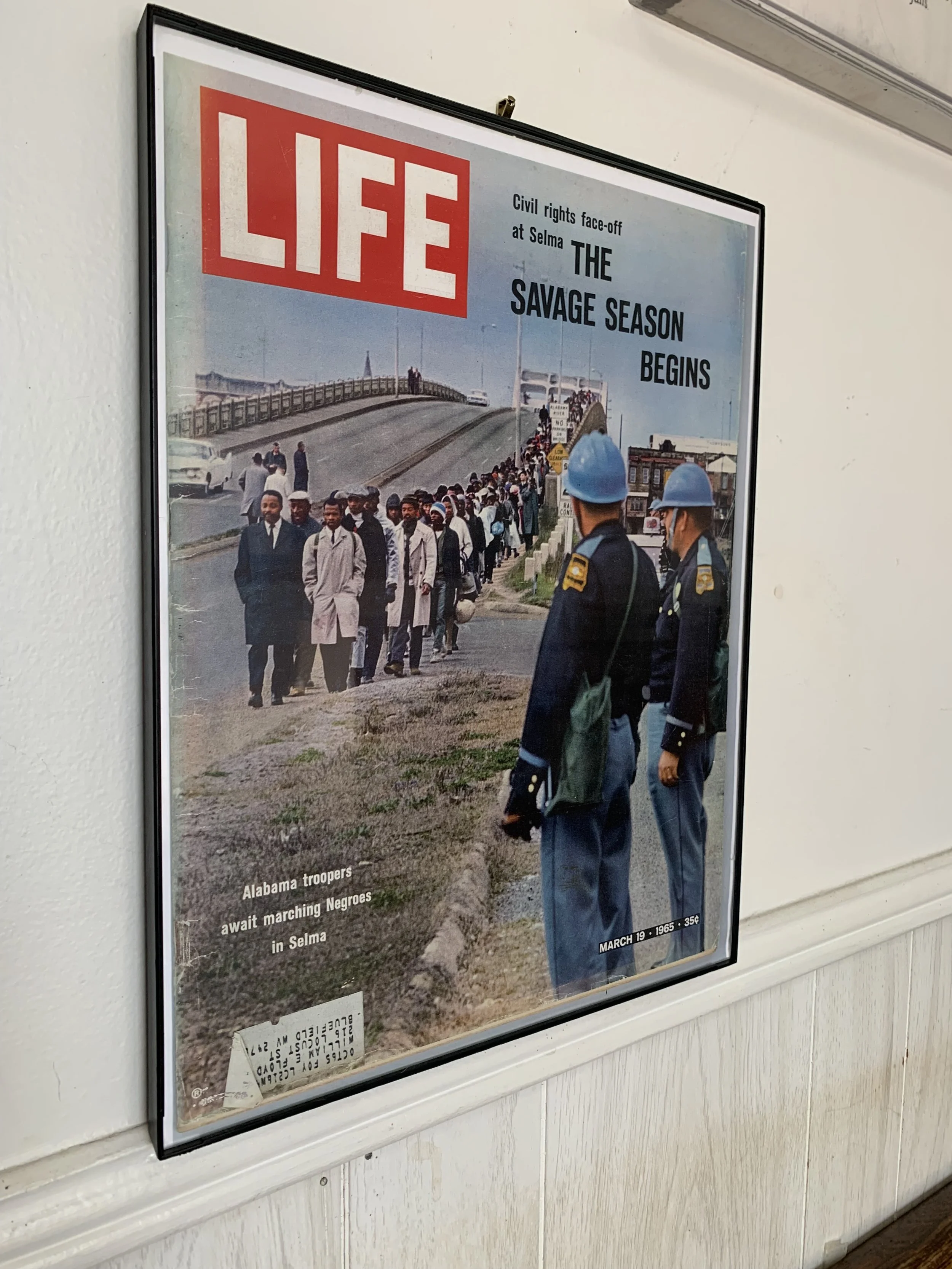

On March 7th, 1965, the so called “Bloody Sunday”, the freedom marchers were brutally beaten trying to cross the bridge. But two weeks later Martin Luther King and thousands of his followers could reach their destination under the protection of the National Guard which President Lyndon B. Johnson had ordered into Alabama after the life pictures on national TV had shown racist state troopers beating, teargassing and trampling the would-be marchers supported a vicious white crowd gathering from all over Dallas County. As a result of this outrage the “Voting Rights Act” was passed by Congress in August 1965 and laid the foundation for Civil Rights Legislation in America.

After his small group’s symbolic crossing of the bridge 60 years on, Reverend Alvin Bibbs is eager to tell us his view of recent history and what it has to do with Donald Trump’s election victory. Born into one of the most crime-infested housing projects on the South Side of Chicago, Alvin’s destiny changed at the age of six, when Martin Luther King on a visit to his local church “stroke his hand over my curly afro head” and gave the young boy his blessing. From then on, Alvin focused on school, won athletes scholarships, played professional basketball in Spain, became a reverend and now heads the “Justice Journey Alliance”, an NGO supporting the cause of civil rights.

Alvin Bibbs has witnessed a decades-long conservative campaign to install fear into “European Americans” who felt that they were losing economic power, influence and status. “This dynamic of fear”, Alvin says, “has moved into rural white communities all over the country”. “And once you have caught that vision”, the black reverend puts himself into the shoes of white voters, “you believe that you have to take back your country again”. And now Alvin Bibbs is seeing the Trump Administration “demolishing the system of civil rights, discrediting and capturing the history of our movement”.

You do not have to be black to understand this dynamic. Laura Jansen, the CEO of another nonprofit organization as part of his tour group, finds even harsher words for what is happening: “Many white Americans have lost shit - pardon my language - when the country voted twice for a black president”. And with that shock of 2008 and 2012 she explains Donald Trump’s success. “Deep down it’s racism couched in other terms”.

At the foot of Edmund Pettus Bridge we meet Charles who works as a guide for the trickle of tourist groups visiting this historic location. One just has to mention the name of Donald Trump and Charles spurts out how “desolate and devastated” he feels about the political backlash in the making. For him 21st of March, 1965, “was the best day in his country’s history, and “November 5th, 2024, was the worst”. He now fears “that the achievements of the civil rights era might be taken back”.

Charles was born here in Selma. He was good in school, going to study law when his daughter was born and “God had another plan for him”. Instead, he worked as a pipe fitter and in warehouses of all kinds. In a state with one of the lowest minimum wages he has witnessed brain drain, white flight, the outsourcing of jobs and local industry dying. According to him it started in 1978 when the nearby army base closed and continues with the shutting down of the Selma AmeriCorps Program just announced a week ago. “We have always been punished for what we did in 1965 and how we have voted since”, he believes, which in November 2024 was 65% for Kamala Harris in Dallas County with its population 70 % black.

Charles disappointment in life seems all-encompassing: from the tourists in Selma “who only gawk at history, but don’t have skin in it”; to the state of Alabama with one of the lowest teacher salaries nationwide for his wife; to the churches catering for white people “who once threw rocks and tomatoes at us with the bible in the other hand”. Whereas the God he believes in, tells you “to love other human beings”. Still, Charles is manning the folding table next to Edmund Pettus Bridge with the literature about Selma and the Civil Rights Movement every day, explaining its history with knowledge and enthusiasm.

“The Selma Times Journal” is located just across the street from where Charles offers his services as a guide. And over the last 25 years its editor Brent Maze has watched the same developments if from a different vantage point. The town’s journal faces the typical economic challenges for local newspapers in the country: a loss of population, a dwindling readership and receding advertising revenue. Seven years ago, it had to change from a daily print run to appearing twice a week and reduce its personnel to a full-time staff of five. Brent Maze, who is white, came to Selma from Jackson, Mississippi, his father being involved in the civil rights movement.

How do they cover race relations? “In daily reporting”, says the editor, “the issue of race is always in the back of your mind. Yet black-on-white crime does no longer automatically make the front page, Brent explains the subtle shift, “unless it is murder”.

Brent Maze is listing the “firsts” in Selma’s recent history: its first black mayor in the late 2000s, President Obama’s visit at the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday” when people lined up as far as two blocks from the bridge; and recently the first black schoolboard, yet with white pupils still escaping to two private schools.

Yet he has also seen backward steps when around 2008 conservative traditional Democrats moved to the Republicans; “when the Obama’s presidency led to white fears of losing their identity”; when single issues like abortion hit the Democratic Party in Alabama and churches preached that you can’t be a Christian and a Democrat at the same time. “The rise of Donald Trump”, he states, “coincided with those white sentiments”.

Looking out from his office window Brent Maze can already notice the immediate consequences of these long-term political changes. There are no longer workers on the building site of the “Selma Interpretive Center” since Elon Musk has imposed cuts on the National Parks Service which was to run this latest addition to the Civil Rights Trail for tourists. And last week the mayor had to announce 55 million Dollars in cuts of federal funding which will further damage the town’s plans for the refurbishments of its infrastructure. The black mayor’s slogan for his election “Rebuild together” is likely to ring hollow soon.

On our one-hour drive from Selma to Alabama we have time to compare what we have heard with what we have read before coming here. For instance, Franz Fanons famous quote “The white man, slave to his superiority” in his book of 1952 “Black Skin, White Masks” where the revolutionary critic of colonialism and psychiatrist writes about white fears of losing a privileged position due to black people’s demands for equality.

Or take Robert Kagan’s recent book “Rebellion” where the author links the anti-liberal strain in American history to race and religion functioning as continuous foundation of white supremacist attitudes and fear. With the election of Barack Obama, Kagan writes, “an open racism not seen in decades reemerged”. “When Donald Trump ran (for the Presidency, R.P.) in 2016 his identity as a white male supremacist was well established”.

As in the town of Selma, the center of Montgomery receives you with eerily deserted streets but many Memorial Sites. Those look like modern shells for a dynamic past as if the gritty fight for Civil Rights had been moved to the safe spaces of impressive museums. Yet the city itself with its 200.000 inhabitants and despite some successful urban revitalization projects still looks like a forlorn Southern space, slow and stubborn, with some pretentious neoclassic office towers but lacking contemporary presence and dynamism.

And the recent changes Dwayne Fatherree notices are not for the better. The veteran journalist who researches and writes for the well-established “Southern Poverty Law Center” (SPLC) has recently been reporting on the local effects of the current decrees by Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

Because the SPLC and most of the historical sites in Montgomery are privately funded they are not being hit by the cutbacks of diversity programs. But quite a few NGOs and monitoring groups in Alabama will be indirectly affected when, for example, cuts in federal housing grants lead to their offices having to close. And the numerous “hate groups”, which the SPLC has been tracking for decades, says Dwayne, “will feel empowered by these new policies”. In the past conservative politicians had a certain philosophy and discipline, the white journalist continues. “Now they are just out to destroy everything that is not them”. And how do the different communities react to the attacks by the new administration? Whilst the white community feel encouraged to practice their passive racism, Dwayne surmises, “people in the black community might think that they have seen it all and that things can’t get much worse.”

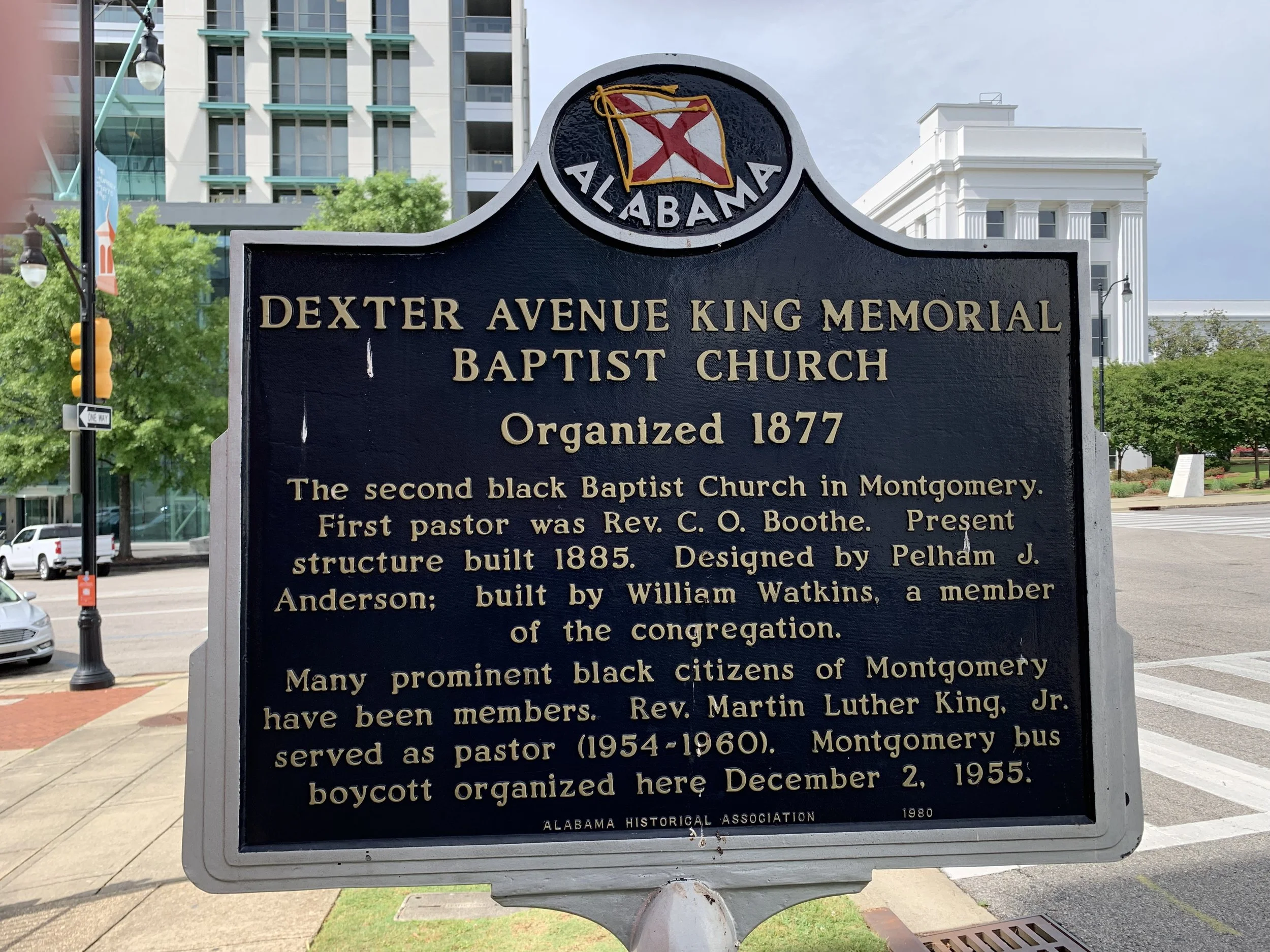

Back in the streets of Montgomery, tourist coaches stop briefly at the “Dexter Avenue Memorial Church” where its former pastor Martin Luther King and the Freedom Riders planned the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the march from Selma; then they empty their loads of mostly black visitors at the interactive “Legacy Museum” and the visually haunting “National Memorial for Peace and Justice”. We will follow that trail.

It is the Sunday morning worship at the “Dexter Avenue Memorial Baptist Church.” The blues-trained organist is hitting the reverberating gospel notes of call and response; the small women choir dressed in white lace sings beautifully and Pastor Allen Sims is preaching emphatically - but all in front of half-empty pews. The history of this engaged church serves no longer as guarantee for contemporary faith. And there are political reasons for that, as Reverend Dr. Allen Sims will point out to us after the service.

Churches, he explains, have shifted from small to mega, with the small churches having struggled through the epidemics of Aids and Covid. And over the years, the pastor explains, “Evangelicals wanted to have a piece of the pie and moved with the Republican party to the right”. He tells you of his “deep disappointment in white pastors he once respected, “staying silent like the universities” in these troubled political times. But Pastor Sims not only chastises his colleagues at the white mega-churches. He also admonishes African Americans “thinking that Barack Obama was our savior”. The ensuing disillusion and distrust, he says, “led to some African American men to not vote for Kamala Harris”.

Today Rev. Dr. Allen Sims - in the long line of “political” pastors following Martin Luther King - sees his nation and its churches “at the crossroads”. Is there hope or no hope? He does not seem to be sure. Given the dedication of those present at the Sunday morning service but also the empty rows in his church, one understands his uncertainty.

Onward to the “Legacy Museum” on the site of a former slave market. Its manifold installations document the story of race as America’s original sin with prosecutorial thoroughness: from slavery, through the eras of Reconstruction and Jim Crow up to the continuous incarceration of black men. What is missing, of course, is the most recent twist of that story, racism’s current reincarnation defined as zero-sum game between the felt loss of white status and the imagined gains by the black or brown race.

Therefore, we ask how some of the visitors link the black experience displayed to today’s political landscape. Given the brutal images of southern history, he has just walked through for two hours, Eddie, a businessman from Atlanta, is angry at “those black brothers who have voted for Donald Trump just for tax relief”. And having passed through the dramatic displays of families ripped apart by slavery, traumatised by lynchings and punished by today’s penal laws his adult daughter believes “that we in the black community will have to focus more on our families”. Together we enter the shuttle bus that brings us to the “National Memorial for Peace and Justice”.

Opened in 2018 this most recent addition to the string of beautifully designed Legacy Sites is an open-sided pavilion visualizing more than 4.400 racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950. Here among more than 800 hundred slabs of rust-colored Corten steel, some suspended, some standing, we meet Anthony and Wendell, two black visitors from North Carolina. Searching and finding the slab listing the lynchings in Nash County Anthony cannot believe what he reads: that in his home county they had lynched 20 black men on the same day with thousands of white spectators watching, as the engraved entry on the rusty surface states. “That happens if you declare the others different as we do with migrants today”, he says still a little breathless from the shocking discovery about his home county’s cruel history.

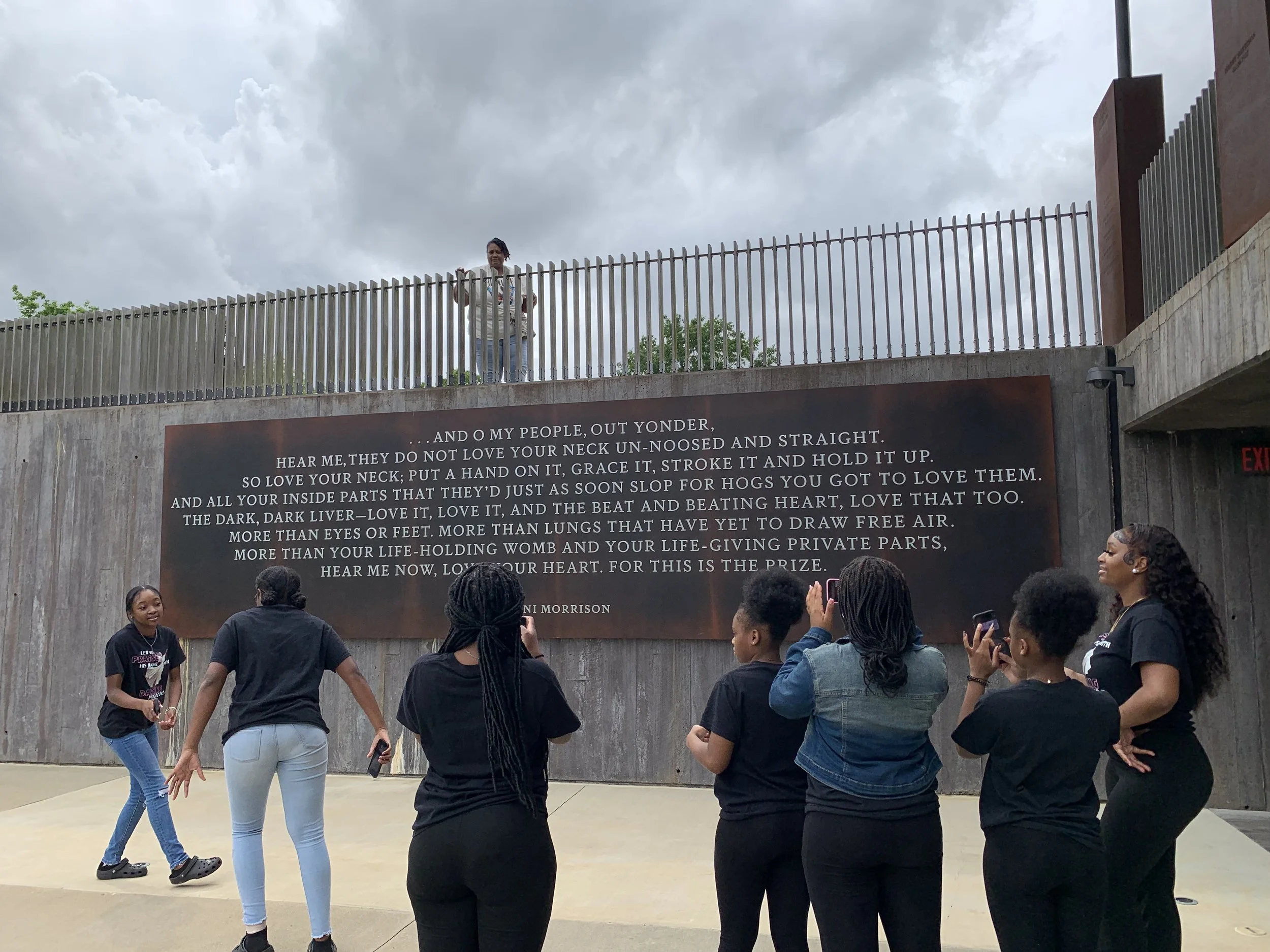

In front of another jarring sculpture in the outside garden overlooking downtown Montgomery we ask Charity, a student at Georgia Tech, how she relates the legacy of the lynchings symbolised by hanging slabs and coffin-like steel boxes on the ground to what is happening to America now.

Charity has come with her family but among the visiting crowd of black school classes and white tourists from up North she is missing the white people of Georgia or Alabama. “The ones who still haven’t understood what systemic racism is. Because we might have the same rights but still face many different obstacles.” And now with Donald Trump, she says with a bitterness not befitting her age, “the affirmative action and diversity programs to help us overcome these obstacles are on the way out”.